Factors Investing opportunities

The expected return of a financial asset can be modeled as a function of various theoretical factors according to three main categories: macroeconomic, statistical, and fundamental. Employing multiple factors addresses their cyclicality and increases diversification. However, there is no free lunch attached to factor investing.

Ross (1976) Arbitrage pricing theory (APT) holds that the expected return of a financial asset can be modeled as a function of various macroeconomic factors or theoretical market indexes. APT did not explicitly state what these factors should be; indeed, the number and nature of these factors were likely to change over time and vary across markets. Thus the challenge of building factor models became, and continues to be, essentially empirical in nature. Fama and French (1992, 1993) put forward a model explaining US equity market returns with three factors: the “market” (based on the traditional CAPM model), the size factor (large vs. small-capitalization stocks) and the value factor (low vs. high book to market).

- Macroeconomic factors include measures such as surprises in inflation, surprises in GNP, surprises in the yield curve, and other measures of the macroeconomy (see Chen, Ross, and Roll (1986) for one of the first most well-known models)

- Statistical factor models identify factors using statistical techniques such as principal components analysis (PCA) where the factors are not pre-specified in advance

- Fundamental factors (Value, Growth, Size, Momentum) capture stock characteristics such as industry membership, country membership, valuation ratios, and technical indicators, to name a few

Factor Investing and risk sources

Risk premia factors (Value, Low Size, Low Volatility, High Yield, Quality, and Momentum) are factors that have earned a persistent significant premium over long periods and that clearly reflect exposure to sources of systematic risk. Instead, factors that do not explain well risk but do earn persistent premia over time are named alpha signals (earnings revisions or earnings momentum). All of the Fama-French factors count as risk premia factors since the aim of those original studies was to isolate asset pricing drivers. Note that the sensitivity of systematic factors to macroeconomic and market forces resulted in some long periods of underperformance; thus, because of low correlations relative to other factors, diversification across factors is fundamental in factor investing to reduce the length of such underperformance.

What drives factor investing returns

In general, factor returns are explained with different approaches. On one hand, factor returns reflect systematic sources of risk in (weakly) efficient markets; on the other one, factor returns derive from investors behavioral biases or constraints (e.g., time horizons, ability to use leverage, etc.).

- Systematic risk perspective. Some risk that cannot be diversified away is paid into a premium. For instance, the small-cap premium reflects scarce liquidity (Liu, 2006), scarce transparency (Zhang, 2006), and more probable distress (Chan and Chen, 1991; Dichev, 1998). Value, Size, and Momentum are linked to country growth and inflation and are sensitive to shocks in the economy (Winkelmann et al., 2013).

- Behavioral biases approach. From behavioral finance literature, the extensive presence of specific investors traits (cognitive or emotional weaknesses) determining behavioral biases results in a prohibitively costly arbitrage, leading to such anomalies (factors). For instance, chasing winners, over-reaction, overconfidence, home bias, and myopic loss aversion.

- Constraints and frictions/flows perspective. Anomalies arise from constraints and industry practice. For instance, investors’ shorter time horizons (3- and 5-year horizons) determine a premium for stocks with low liquidity over long horizons (10 years plus). Baker et al. (2011) consider the use of institutional benchmarks, and the subsequent preference for relative returns, as one reason why the low volatility premium exists. Dasgupta, Prat, and Verardo (2011) argue that reputation concerns cause managers to move together generating momentum under certain circumstances.

Among the explanations of the returns of factor investing, the industry subscribes to the systematic risk; however, academics are more oriented towards the behavioral and constraints perspectives. However, in the latter case, factors persistence is relative to the persistence of investors’ biases and constraints.

One important critique of factor investing is that the factors that deliver premia do not always have clear economic interpretations. Although some factors, such as credit and term structure risk, are easily linked to risks which investors naturally seek to avoid or insure themselves against, others, such as momentum, are puzzling. Unfortunately, the factors that appear to explain the most cross-sectional variation in historical stock returns are also those with the least economic intuition.

Application: Fama-French Three Factors

The Fama-French model employs market, size (SMB), and value (HML) to calculate the expected portfolio returns. According to K. French webpage,

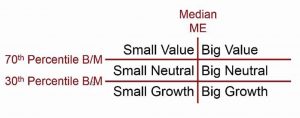

all returns are in U.S. dollars, include dividends and capital gains, and are not continuously compounded. To construct the SMB and HML factors, stocks in a region are sorted into two market cap and three book-to-market equity (B/M) groups at the end of each June. Big stocks are those in the top 90% of June market cap and small stocks are those in the bottom 10%. The B/M breakpoints for a region are the 30th and 70th percentiles of B/M for the big stocks.

- (Rm – Rf) is the return on a region’s value-weight market portfolio minus the U.S. one month T-bill rate. The factor for July of year t to June of t+1 include all stocks having available market equity data for June of t

- SMB is the equal-weight average of the returns on the three small stock portfolios for the region minus the average of the returns on the three big stock portfolios. The factor for July of year t to June of t+1 include all stocks having available market equity data for December of t–1 and June of t.

- HML is the equal-weight average of the returns for the two high B/M portfolios for a region minus the average of the returns for the two low B/M portfolios. The factor for July of year t to June of t+1 include all stocks having available (positive) book equity data for t–1.

How to use Factor Investing

Market capitalization-weighted indexes represent the opportunity set of investors, the most effective benchmarks, and the only reference for a truly passive, macro consistent, buy and hold investment strategy with high trading liquidity and relatively low turnover of stocks. Factor indexes reflect the performance of equity risk premia factors in order to allow factor allocations to be implemented passively. The main issues involved include:

- the documented cyclical periods of underperformance that require either long-term investing or diversification within factors by employing multiple factors (for instance, Quality, Momentum, and Value). Ang and Kjaer (2011) and Blitz, Huij, and Steenkamp (2012), among others, argue that factor investing is a good long-horizon strategy, particularly for institutions that are not sensitive to occasional periods of poor returns.

- the methodology employed to capture systematic factors through indexes: the choice of stock universe, weighting scheme, and rebalancing frequency. For instance, an index including all constituents with reweighting has lower tracking error and exposure than an index including a subset of highly factor-relevant constituents.

First, factors should be thoughtfully selected and combined. For instance, the momentum factor seems to work well during expansions, whereas the quality and volatility factors perform better during contractions. Accordingly, an investor seeking to maximize profits will tilt his portfolio to momentum during expansions; instead, another investor willing to decrease risk will tilt to value. Note that quality (or value) and momentum are negatively correlated, thus they can be effectively combined and perform better than the single factors.

Second, factors components should be optimized within the portfolio. Single-factor portfolios, which are strategies that invest in stocks that score highly on one particular factor, are generally suboptimal because they ignore the possibility that these stocks may be unattractive from the perspective of other factors. According to Bender and Wang (2016), a portfolio created using single-factor components (top-down) is less efficient than a multi-factor portfolio built from the security level (bottom-up). The latter approach would seem to be better because the portfolio weight of each security will depend on how well it ranks on multiple factors simultaneously; additionally, the volatility of the bottom-up portfolio was significantly lower. The justification may reside in the fact that the approach combining single-factor portfolios may miss the effects of cross-sectional interaction between factors at the security level. However, Blitz and Vidojevic (2018) noted that single-factor strategies show negative contributions from other factors resulting in substantial weight in stocks with negative expected and ex-post realized market-relative returns. However, a simple optimization consists of removing stocks that have lower expected returns than the market, based on their overall factor profile.

Third, multi-factor portfolios should be rationally managed. Factor investing should be implemented through mean-variance optimization because it will select the best allocation across multiple factors. Risk parity, an approach advocated by Bridgewater, AQR, and Rebeco, equalizes the risks of the two factors to improve diversification and to potentially increase expected returns. By scaling up one factor through leverage it increases expected return but also exposes the portfolio to additional liquidity risks; indeed, levered positions may become difficult to maintain. Risk parity is an arbitrary choice to maintain equal risk exposure—not the best choice. The mathematics of the Markowitz model insures that simply putting the factors into the program will dominate risk parity.

Know Factors in Literature

Macroeconomic factors (GDP, credit, interests, etc.) may help in explaining the return across asset classes, whereas fundamental factors (volatility, momentum, quality or value, etc.) may help in explaining the returns within asset classes.

TERM STRUCTURE FACTOR. Long-term government bonds have historically provided higher yields than short-term bonds, and this difference can be regarded as a premium for the exposure to the risk of variation in the future short-term rate or to the variation in demand for money at different maturities.

CREDIT RISK FACTOR. This captures the compensation for the risk of default on debt instruments. For corporate debt, it is likely to be correlated to the equity premium, because defaulted debt becomes equity. It has also a macroeconomic component because defaults tend to be clustered in time and occur in periods of financial distress.

FOREIGN EXCHANGE CARRY. This factor captures the return to lending in high-interest currencies and borrowing in low-interest currencies. This strategy has an implicit premium due to the risk of interest rate convergence, but its use has been documented only over the modern era for which currencies have traded in the capital markets, which is the post-1970s periods, after the breakdown of Bretton Woods.

VALUE FACTOR. This is typically constructed from a long position in stocks with a high book to market ratio and a short position in stocks with an unusually low book to market ratio. Other accounting variables (earnings, sales, forecasted and realized earnings) can be used. An economic interpretation of this factor is that it represents compensation for firm distress.

SIZE FACTOR. Constructed from a long position in small-cap stocks and a short position in large-cap stocks is well documented in the literature but not clearly justified.

MOMENTUM FACTOR. As with the value premium, this factor has a very strong historical premium but no clearly articulated risk. It is somewhat related to a strategy long used in practice called buying on relative strength and analyzed by Jegadeesh and Titman (1993). Explanations are behavioral, based on investors underreaction to the news. Momentum profits turn negative during an extended bear market—the implication being that bull markets attract naïve investors whose slow price equilibration may be exploited by simple investment rules. The momentum factor crashed during the financial crisis, indicating that the steady profits it gained over long stretches of time may compensate for episodic but extreme risks. Momentum appears to be pervasive in nearly every asset class, within each asset class, and even across asset classes.

VOLATILITY FACTOR. A volatility premium arises, among other reasons, because agents are averse to periods of increased volatility and are willing to pay high prices to hedge against significant increases in market volatility—which typically also coincide with downward market moves (cf. Bakshi and Kapadia, 2003). A volatility factor manifests itself in the cross-section of options: out-of-the-money options are expensive compared to at-the-money options (cf. Coval and Shumway, 2001).

LIQUIDITY FACTOR. Liquidity, or the ability to trade a security quickly and with little impact on the market price, is a well-known risk in capital markets. The financial crisis in 2008 was characterized by a massive reduction in liquidity for certain instruments such as mortgage-backed securities. Even prior to the crisis, strong empirical evidence suggested that illiquidity arose in periods of financial distress. Researchers and practitioners have hypothesized that illiquidity is, therefore, a priced factor that can deliver a premium to investors able to withstand illiquid episodes in the capital markets.

INFLATION FACTOR. Expectations of future inflation are embedded in the yield curve because most bonds— except TIPS—are contracts in nominal terms. Chen, Roll, and Ross (1986) found that two inflation-related factors were priced in the cross-section of stock returns: inflation surprises and change in expected inflation.

GDP FACTOR. Cochrane (1999) observes that the economic effects of booms and recessions in the economy are so pervasive that exposure to fluctuations in the GDP should command a risk premium. Chen, Roll, and Ross (1986) found a premium for a factor constructed from shocks to industrial production, despite the econometric difficulties in measuring macroeconomic variables. More recent tests have found some evidence that a procyclicality factor may explain differences in stock returns.

EQUITY RISK PREMIUM. It is important to include the equity risk premium because the spread of stock returns over bond returns has been empirically documented over centuries of stock market returns.

PROFITABILITY. A measure of profitability is defined as gross profits minus the total costs of goods sold; thus, stocks of high profitable companies are assumed to generate more returns than low profitable companies. The difference between the returns of a portfolio of high-profitability stocks (Robust) and low-profitability stocks (Weak) is called Robust minus Weak or RMW.

INVESTMENT. A measure of investment is defined as the growth in total assets; thus, companies with low growth in total asset are assumed to generate more returns than companies with high growth in total asset. The difference between the returns of a portfolio of low asset growth (Conservative) and high asset growth (Aggressive) is called Conservative minus Aggressive or CMA.

References

E. Elton, M. Gruber, S. Brown, W. Goetzmann. (2007). Modern Portfolio Theory and Investment Analysis, 11th edition.

J. Bender, R. Briand, D. Melas, R. A. Subramanian (2013). Foundations of factor investing.